|

Being one of the

first deserted medieval settlements to be extensively excavated, the site of

Seacourt promised to provide important evidence in connexion with the

chronology of medieval pottery and small finds.

Additionally, the

excavations, notably those in the line of the impending Western by-pass

project in 1938/39 by Rupert Bruce-Mitford and then later

in 1958/59 by Martin Biddle, cast new light on medieval

economic history and of conditions at the end of the 14th

century when important changes were taking place in the status of the

English peasantry.

|

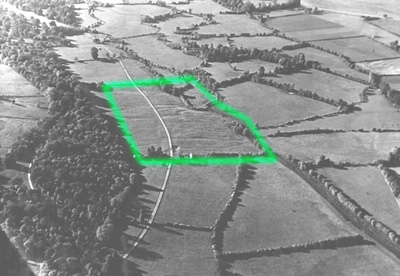

Figure

2.

Seacourt, 1938/39

Seacourt Area Oblique Photograph, 1951, (Courtesy

of Allen Aerial Photographic Archive)

Place:

Seacourt

DMS

NGR:

SP

460 080

Parish:

Wytham

District:

Vale of White Horse

County:

Oxfordshire

|

|

|

Chronology

The position of the early

nucleus of settlement has not so far been located. It may have lain in the

south-eastern part of the village; however, the trial trenches dug in 1939

did not reveal any clear indication of dates earlier than the 12th

century.

The evidence from Areas

1,2,5,6 and 11 suggest the village expanded greatly to the north and

west towards the end of the 12th century, reflecting the

rising population and land hunger which reached its height in the later

13th century (Beresford, 1954). During this time, a shift

from timber construction towards that of stone was observed.

Economy

Apart

from the probable byre in Area 1 and the wooden barn-byre in Area 5,

the structures excavated at Seacourt were dwellings. The only traces

of industrial processes were those of iron-smelting in Area 31. Agriculture

and animal husbandry were clearly the main occupations.

|

The Seacourt house

The early 13th

century house in Area 5 is so similar in size and plan to the later

stone houses that it may be safe to assume it is representative of the

typical Seacourt house. It is a rectangular structure, about 25 ft by

14 ft internally, with a single hearth either centralised or against

the middle of the rear wall, with no sign of any partitions or walls.

In no cases were enough roof-tiles found to suggest anything but a thatched

roof.

Unlike the typical medieval

long-house, the Seacourt houses had no provision for accommodating animals.

Instead, it seems likely that animals were kept in subsidiary buildings,

examples of which have been associated with most of the stone houses and

also the timber house of Area 5. The origins of this type of farm-unit,

surely differing from those which gave rise to the long-house, at present is

unclear.

|

|

Village

planning

There is little evidence

for a coherent plan of the village until the middle of the 13th

century, at which time the paving of the north-south street defined

the future main access of this part of the village. However, timber

structures in Areas 1 and 5 suggest positioning about an earlier boundary

of the same location. All the excavated stone buildings seem to be laid

out in relation to this north-south street, on to which the doors of

the houses probably opened. In some cases, the houses seemed to have

faced each other, as if laid out in pairs.

|