|

A Vessel for everyman and his family |

| Note: Although this file is designed to be printed out, its exact format will depend on the page setup of your browser. Note: There are nine images on this page. |

| List of Contents |

| What purpose did it serve? |

| How is a vessel defined? |

| Changing fashions |

| Dated parallels |

| Acquiring the vessel |

| Bibliography |

| What purpose did it serve? | |

| Containers were used for the preparation of food, storage, eating and drinking, serving at table, dispensing medicines, industrial needs and even as funerary urns. | |

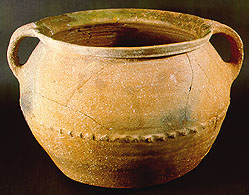

| Regional variations in ceramic forms abound; there are marked differences between that most functional of forms: the jar, used for cooking and storage. These technically unsophisticated wares met consumer demand over a very long period. Jugs became numerically more abundant in the thirteenth century. Materials other than clay were used at other times for storage and cooking, including wooden barrels and metal cooking vessels. |

Large shouldered jar, glazed around the rim only |

| How is a vessel defined? | ||

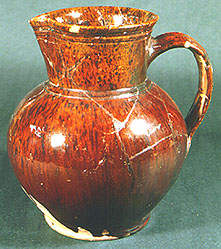

Baluster jug with strap handle. The earthenware was waterproofed by a thin light green glaze |

Ceramic forms can be classified according to shape or profile. There is considerable variety in size and height and therefore in capacity. The site of the New Bodleian, Oxford included tall, closed vessels where the diameter of both the opening and the maximum girth are smaller than the overall height; these are defined as jugs for serving and standing at table. They are handled vessels, often with a pouring lip or spout. Jugs can be further classified on the basis of the vessel profiles and by their proportions. |

Biconical jug with strap handle. The upper part is decorated with applied strips of iron-rich clay

and a thick, glossy yellow glaze

Biconical jug with strap handle. The upper part is decorated with applied strips of iron-rich clay

and a thick, glossy yellow glaze

|

| Changing fashions | ||

| An astonishing variety of decorative styles was present by the thirteenth century. Serving vessels often display a masterly sense of design, allowing colourful motifs on vessels to be enjoyed by the full range of society. Quantitative analysis has revealed a preference for mottled green glaze in everyday life, through three centuries. Visual imagery including colour was all important to medieval man, who must have been adept at interpreting almost everything symbolically. |

Puzzle jugs were designed for communal drinking games |

|

Shouldered drinking jug and lobed cup for communal drinking, decorated with mottled green glaze |

||

| The development of ceramic stylistic innovations shows some periods of continuity and others of change. Fluctuations in design and technology are influenced by the social and functional differentiation between consumers and regional and continental economic links and their political requirements. | ||

| Dated parallels | ||

| Salt-glazed Raeren stoneware drinking vessels are depicted in numerous contemporary paintings: such an example is The Wedding Feast painted by Pieter Brueghel in the late 1560s. (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) |

Raeren stoneware drinking vessels, one with a vertical loop handle and the other with a strap handle |

|

Blackware flared mugs with vertical loop handles |

||

| These Blackware mugs with single or double vertical loop handles are decorated with lead glaze which probably drew iron from the body of the clay, giving rise to a dark colour. It is recognised in Staffordshire from deposits of the mid 17th century. Two of the illustrated vessels were found in association with a porringer made on the Surrey/Hampshire border, identical to one found with a hoard of coins deposited around the 1640s. | ||

|

Acquiring the vessel

A family might have bought vessels from a market stall, either paying in cash or exchanging products that they had produced themselves. Hawkers (door-to-door salesmen) operated in many areas; fairs and seasonal festivals provided important mechanisms for exchange. Otherwise, ceramic vessels may have been purchased directly from the potter at a production centre. In the later medieval period it became possible to buy pots from shops. This variety of acquisition methods generates complex patterns, but some broad trends can be seen when vessels or fragments of pottery sherds from a major production centre are plotted. |

Shouldered jug in Mottled Brown ware was probably a regional import |

Money boxes discarded together in Oxford, perhaps representing the old stock from a shop |

| Bibliography | |

|

D. Barker, "North Staffordshire post-medieval ceramics - a type series. Part two: blackware",

Staffordshire Archaeological Studies 3 (1986), 58-75

M. Mellor, "A synthesis of Middle and Late Saxon, medieval and early post-medieval pottery in the Oxford region", Oxoniensia 59 (1994), 17-217 MPRG, A Guide to the Classification of Medieval Ceramic Forms Medieval Pottery (1998) J. Pearce, Post-Medieval Pottery in London 1500-1700, vol. 1, Border Wares (1992) The Curator of Reading Museum, "A find of Stuart coins at Childrey Manor, Berks", Berkshire Archaeological Journal 41(1937), 82-84, pl. II |

|

© Copyright University of Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, 2000 The Ashmolean Museum retains the copyright of all materials used here and in its Museum Web pages. last updated: jcm/15-mar-2000 |