|

Fingerprints of the maker |

| Note: Although this file is designed to be printed out, its exact format will depend on the page setup of your browser. Note: There are six images on this page. |

| List of Contents |

| What did the potter need? |

| Why did they adapt the clay? |

| The making of the vessel |

| Decorative techniques |

| How were pots fired? |

| Smart potters succeed |

| Bibliography |

| What did the potter need? | |

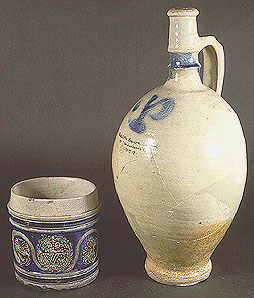

| The raw materials necessary for the production of pottery are clay, water and fuel. Fillers and decorative materials may also be used. The properties of the clay derive from the parent rock. There are two types of clay: primary clay is acquired directly from the parent rock and is found in the place of its origin; secondary clay is decomposed rock which is weathered and deposited elsewhere. During transportation by glacial action, by river or by sea, clay picks up impurities and finally settles into beds of similar-sized particles. Stoneware clays form an example of secondary clay. Stoneware vessels were imported into England from France and the Rhineland, until the English learned the secret of making stoneware in the later seventeenth century. |

Westerwald Stoneware made from secondary clay associated

with Coal Measures (fireclay)

Westerwald Stoneware made from secondary clay associated

with Coal Measures (fireclay)

|

| Why did they adapt the clay? | |

| Earthenware clays are also secondary clays, and are many and various. This is the most common clay type used in the pottery recovered from archaeological excavations from the Neolithic to the late medieval period. The potter would choose the best clays and adapt it for the task ahead. Some vessels needed to be fireproof, others non-porous. Inclusions are added to "open" the clay or to improve the firing of a vessel. |

Clay diggings on Brill Common in Buckinghamshire have

changed the landscape

Clay diggings on Brill Common in Buckinghamshire have

changed the landscape

|

| The making of the vessel | |

| The manufacturing processes were complex and each stage presented a design choice. Vessels thrown on a wheel have the potential to be more symmetrical than if handmade. Handles and spouts often reflect the personal technique of an individual potter. Following its abandonment at the end of the Roman period, the potter's wheel was reintroduced from the eighth century onwards, enabling the potters to meet the needs of the growing urban communities. As late as the nineteenth century, however, some country potters continued to build their pots by hand. |

A rounded wheel-thrown jar or waster (an overfired vessel) from a kiln excavated at Brill, in Buckinghamshire |

| Decorative techniques | |

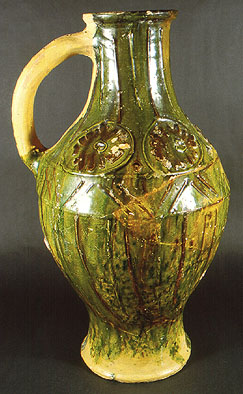

| Surface treatment and decorative techniques can give insights into the quantity and quality of the workers engaged at a production centre in this labour-intensive craft. Decorative motifs may reflect the environment familiar to the potter, a family trademark or a reference to the intended use. They may also indicate social hierarchies, group identities or social status of the perceived consumer. Alternatively their eye-catching appearance may have been designed to promote sales. Glazes in the medieval period were mainly lead-based, forming a yellowish-green vitreous surface. Mottled green and bright green colour was achieved by adding copper to the glaze. The craftsmen potters of the Brill/Boarstall production centre, strong market-leaders in the thirteenth century, showed great freedom of artistic expression. This suggests sound capital investment in a dynamic, well organised industry. |

The stimulus of this decorative jug may be derived from life in the forest where the potters gathered their fuel |

| How were pots fired? | |

|

Medieval forms and clay types were less standardised than nineteenth-century

industrialised production. Fired clay vessels have a range of colours,

depending on mineral inclusions and the firing temperature. Sap in the

brushwood or tree loppings, at different seasons, affected the final

colour of the fired clay and the colour of the glaze. Such variations

were frequently unintended, but some wares show a consistency that suggests

an impressive level of control by the potter.

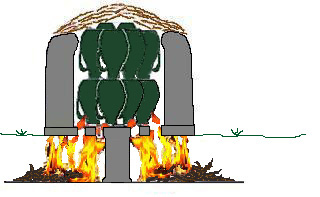

Much pottery was fired in a bonfire or pit with no permanent super-structure. The pots were generally fired upside down. A later development was the "ring-wall" kiln type where the fuel and the wares share the space within the wall and are covered with waste sherds or clay during firing. A further development was the updraught kiln, in which the fuel was confined in a fire-pit, the wares being supported above it on a perforated floor. This type of kiln was fed by single, double or multiple flues. |

|

| Martyn Jope excavated the site of a medieval pottery kiln at Brill, during the summer of 1953, on behalf of the Ashmolean Museum. The kiln was fired from both sides (double flues), a fire being lit at each end. This was the first time such a kiln type had been recognised. The pots were stacked on the firing platform and were probably covered by a clamp of brushwood and clay. This kiln dated to the fourteenth century, but was built on top of at least two others dating to the second half of the thirteenth century. Great quantities of wasters, including many almost complete pots, both glazed and unglazed were recovered (see "The making of the vessel"). | |

Cross-sectional diagram showing the flames and hot gases of the double flue kiln drawn up on to the firing platform |

|

| The site was discovered through the presence of pottery wasters and areas of black, ash-rich soil. |

| Smart potters succeed | |

| The repertoire of vessels and their distribution patterns reflect the economic drive of a production centre. Rising incomes in the thirteenth century encouraged the demand for "packaged" foods, such as butter in pots. By anticipating consumer demand with innovation and marketing, certain pottery workshops succeeded. Such an example is the production centre at Brill/Boarstall which dominated the local ceramic market for some 500 years. |

Novelties captured the townsmen's imagination

Novelties captured the townsmen's imagination |

| The social status of the potters and their families can be explored through interpreting the processes of imitation, innovation and "style drift". This helped to spread new designs and new products. Conclusions from such studies can be substantiated by the techniques of ethnoarchaeology in modern craft-based communities. Our understanding of the production techniques can be explored by means of field experiments and reconstruction. | |

| Bibliography | |

|

E. M Jope, "Medieval Pottery Kilns at Brill, Buckinghamshire: Preliminary Report

on Excavations in 1953", Records of Buckinghamshire 16 (1953-60),

39-42

M. R. McCarthy and C. M. Brooks, Medieval Pottery in Britain AD 900- 1600 (1988) O. S. Rye, Pottery Technology (1988) C. Orton, P. Tyers and A. Vince, Pottery in Archaeology (1993) |

|

© Copyright University of Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, 2000 The Ashmolean Museum retains the copyright of all materials used here and in its Museum Web pages. last updated: jcm/15-mar-2000 |