|

The ABC of pottery in archaeology |

| Note: Although this file is designed to be printed out, its exact format will depend on the page setup of your browser. Note: There are nine images on this page. |

| What is it? | |

| There are three types of ceramic in the archaeological record: earthenware, stoneware and porcelain. All are made from clay, a plastic mineral whose physical structure can be changed permanently by the application of heat. Earthenware is fired to a comparatively low temperature (above 600°C) with the result that it remains porous. Stoneware has a fused, waterproof body achieved through firing above 1200°C., while porcelain is white and translucent, fired at temperatures above 1300°C. Only clays from certain sources can withstand these higher temperatures. |

|

| Still-life by Harmen van Steenwyck (1612 after 1656) with an earthenware jar, earthenware dish with a knife, a pewter-mounted stoneware bottle and a porcelain dish of peaches and grapes | |

| Why is pottery useful to archaeologists? | |

|

Pottery is durable and survives well

in quantities large enough to be useful in statistical analysis. Frequently

it is the most abundant class of material recovered in the course of

archaeological investigation. It can be studied through documentary,

art-historical, chemical, physical and archaeological techniques, leading

to the formation of typological and chronological sequences. An early

example of a typological series was achieved at Oxford on material in

the Ashmolean's collection, from excavations at the New Bodleian Library.

Pottery is also a reflector of the social and physical environment in which it was made and used, and is therefore an indicator of change in social traditions and social patterning. It is an important resource for interpreting the past |

Baluster type jugs, a key product, from the innovative

Brill/Boarstall workshops in Buckinghamshire can be arranged

into a typological sequence

Baluster type jugs, a key product, from the innovative

Brill/Boarstall workshops in Buckinghamshire can be arranged

into a typological sequence

|

| Where does it come from? |

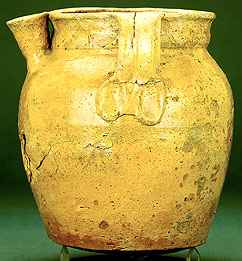

Small rounded earthenware jar, made at the Brill/Boarstall

production centre in Buckinghamshire

Small rounded earthenware jar, made at the Brill/Boarstall

production centre in Buckinghamshire

|

| In the composition of its clay, pottery carries a fingerprint of the geological outcrops of the area where the clay was dug, and petrologists can help seek that source. Locally available filler was added to some clays and this may also help to "source" the vessels. By these means, pottery found in Oxford has been traced to sources all over Europe. |

| How was it made? |

Wheel-thrown biconical bottles and a saucer lamp decorated

with mottled green glaze

Wheel-thrown biconical bottles and a saucer lamp decorated

with mottled green glaze

|

| Every vessel is capable of communicating details of its manufacture, whether hand-built or wheel-thrown, and the technology of its decoration, its glazing and how it was fired. It can also inform us about contemporary craftsmen (and women), and about the economic conditions of their communities. Larger studies can show how production was organised in the countryside and, more rarely, in the town. |

A wheel-thrown Stamford type spouted pitcher, made from fine estuarine clays in south Lincolnshire and excavated in Oxford. Its ownership may have carried a powerful social signal in the eleventh century (Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum) |

By comparing the find-spot with place of origin, we can map patterns of distribution, demonstrating marketing and exchange systems which can be compared with models deduced by historians and geographers for other commodities which survive less well. |

| How was it used, and by whom? |

A spouted pitcher with thumbed base used as a decanter

at table

A spouted pitcher with thumbed base used as a decanter

at table

|

| Among the products of the ceramic industry are a variety of vessels, broadly divided into coarsewares and finewares. Coarsewares are made from ill-sorted clays, while finewares are made from fine-textured, clean clay. Coarseware vessels were used in the home for cooking and storage while finewares were reserved for serving at table or for display; ceramic vessels were also used in the workshop and the pharmacy as containers and in the laboratory for scientific experiments; everyone had a use for ceramic vessels. |

A tinglaze ring vase, with an iconographical sacred

monogram, "IHS", the abbreviation in Greek

of the name of Jesus

A tinglaze ring vase, with an iconographical sacred

monogram, "IHS", the abbreviation in Greek

of the name of Jesus

|

The varying size, shape and form of pottery vessels, as well as their decorative styles, reflect the tastes of everyman and his family. For later periods they can sometimes be matched by art historians with records provided by contemporary illustrations. Visual quality gradually became more important than function alone. The symbolic properties of vessels are less easily interpreted, but are a vital component when studying past lifestyles. |

| What happened to the pottery between discard and discovery? | |

| The surviving fragments from controlled excavations also tell a story of what happened after the vessel was abandoned (usually broken) and before it was rediscovered. Dispersal patterns of sherds from the same vessel may reflect the routine activities of the household or the organisation of a settlement. |

Thumb crucibles, many near complete, discarded after use

together in one area in central Oxford

Thumb crucibles, many near complete, discarded after use

together in one area in central Oxford

|

| How old is it? How long was it in use? | |

| Pottery is common enough to be found in a continuous series of datable associations. These may be established through stratigraphic sequences to a range of independent dating mechanisms, for instance documentary evidence, coin evidence and scientific dating techniques. On rare occasions the vessel itself may include a date, as illustrated here. This vessel was probably a special commission to celebrate an anniversary. |

A Staffordshire type slipware, a posset pot dated 1702,

a special commission

A Staffordshire type slipware, a posset pot dated 1702,

a special commission

|

| © Copyright

University of Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, 2000 The Ashmolean Museum retains the copyright of all materials used here and in its Museum Web pages. last updated: jcm/27-jun-2000 |